LSTS books of the year

Every year, the members of the Law, Science, Technology and Society (LSTS) Research Group of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) are invited to reflect on the books that have influenced the most their (academic) lives and/or have been inspirational.

As per tradition, here are our best reads of 2019, listed in alphabetical order.

See the following links for the editions of 2018, 2017 and 2016.

BERTIN, JACQUES - LA GRAPHIQUE ET LE TRAITEMENT GRAPHIQUE DE L’INFORMATION (ZONES SENSIBLES, 2017)

This is a 2017 reedition of a 1977 book by the French cartographer and theorist Jacques Bertin, devoted to what he called ‘la graphique’. I had never heard of this concept, or about Bertin, but I found this book simultaneously instructive, confusing and exhilarating.

Basically, his message is that there is something called ‘la graphique’, which is different from ‘le graphisme’, mainly because the former would be about relations, as opposed to the latter. Once this is established, the volume takes great care in advancing three points of the highest relevance.

First, it emphasises the links between data visualisation and decision-making: the argument being here that we process and visualise data in order to take decisions, necessarily some type of decision, even if we might not know in advance exactly which decisions we might end up taking. Second, it stresses that for ‘la graphique’ to work at all, it is crucial not just to generate some graphic representation of information, but also to allow permutations of such representations: this, Bertin suggests, shall be enabled for instance by folding marked papers in a certain, special way, that allows easily moving them around in a constructive way; computers, he notes, could also be of use for visualising permutations, but he warns it becomes then very important to make sure one looks at the screen long enough to make sense of what is visible. Third, and closely related to the previous point, Bertin keeps coming back to the question of what is automatable, and what is not.

This fundamental question sounds even better in French, as it is phrased as what is ‘automatisable’, a word that keeps reminding me of my favourite French word, which is ‘frigotartinable’, a notion which might appear to have no relation whatsoever with the subject we are now discussing here, but which also takes us somewhere deep inside the connections between language, technology, and understanding. In sum, this discussion of ‘la graphique’ is, I would say, fully pertinent in our currently AI-obsessed (academic) life. Also, the book has plentiful of only partially comprehensible graphics, a few but very cool pictures, and marvellous titles like ‘Autopsie d’un exemple’ – pure poetry.

Gloria González Fuster

CABANNE, PIERRE - DIALOGUES WITH MARCEL DUCHAMP (BELFOND, 1967)

Because I consider a ‘best of’ books’ list for any given period sensitive personal data (to me, much more sensitive than any on the respective GDPR list, thus empirically proving how outdated their idea is), I am only going to discuss what I am reading right now (by itself a selection, because I am one to stop reading a book midway if it ceases to interest me): Pierre Cabanne’s ‘Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp’. The book is as much an official catalogue of Duchamp’s art as an exercise on morals, the latter being of more interest to me. As with any book by now, it reads better with ready access to the internet both for lookup and for note-keeping purposes. What never ceases to astonish me page after page after page is that both the interviewer-author and the artist have an unspoken understanding on what exactly is the purpose of the book: Duchamp died a couple of years after the book’s completion.

Vagelis Papakonstantinou

CHAGALL, MARK - MY LIFE (PAN-PRESSE, 1922)

Mark Zakharovich Chagall was an early modernist Russian-French artist living and working for almost the whole 20th century. He wrote ‘My life’ when he was 35 and was going to move from Moscow to France during the early years of the post-World War I period. The very long life and the character of the artist himself are worthy of description in the book. However, what makes it really brilliant is the writing (sic!) talent of the artist. Reading the book, one gets the feeling that it was written by a very wise child. The language of the book is as beautiful as the paintings of the author. Chagall had a life full of love, adventures, happiness, but also losses, struggles and failures. Having different circumstances and situations in his life, Chagall was always led by the love for art and by deep respect for his roots.

‘My life’ is the story of his fight for the right to be himself. A sad fact about the book: initially, it was written in Russian and then translated to German. Unfortunately, the first Russian version of the book was lost and the only one available nowadays is the translation back to Russian from a German translation of the original.

Anastasiya Kiseleva

CHEKHOV, ANTON - DAMA S SOBACHKOY [THE LADY WITH THE [LITTLE] DOG] (RUSSKAYA MYSL, 1899)

Here I wanted to reflect more on the form than on the contents. Chekhov was one of the masters of small literary forms. (So was Borges – especially with his ‘Del rigor en la ciencia’, Kapuściński – with his six volumes of ‘Lapidarium’, and many more.) His short stories or novellas, often written using very plain words, spread on but a few pages. In each of his writings, the story he told and the message he tried to convey is powerful and spreads far beyond these few pages.

Obviously, there is a place for both short and long forms in any type of writing, but the point is that Chekhov, Borges or Kapuściński remind us that – sometimes – we don’t need a lengthy or complicated text to say something.

Dariusz Kloza

CHINEN, NATE - PLAYING CHANGES: JAZZ FOR THE NEW CENTURY (VINTAGE BOOKS, 2019; FIRST EDITION: PANTHEON BOOKS, 2018)

When I was a teenager (before the digital age), there was mega-selling weekly music press and music journalists were lifelines for aficionados of any music genre. Things have changed a lot since then, but thankfully we still have access to quality music journalism in print form. ‘Playing Changes: Jazz for the New Century’ is a book by former New York Times jazz critic and NPR contributor Nate Chinen. Working as a jazz critic and covering the music on a day-to-day basis, Chinen is ‘on the ground’ and in ‘Playing Changes’ he takes us along as he watches recording sessions, goes to shows, visits musicians and engages them in conversation.

Taking a broad view of the current moment of jazz, the book’s core argument is that we have been living since the turn of the century in “a brilliant new evolutionary phase” of jazz. Chinen focuses on artists who are pushing jazz into new directions, including Vijay Iyer, Kamasi Washington, Esperanza Spalding, Brad Mehldau. While doing this, he connects them with jazz lineage and places them within a historical context.

Throughout the book, Chinen takes up many themes and subjects including the process of the institutionalization of jazz, black music, jazz education and the confluence of musical styles from around the globe. ‘Playing Changes’ reads like a work of jazz advocacy. With his clear arguments, as well as eloquent and evocative prose style, Chinen show us that jazz is alive, relevant, resilient, polyphonic, fluid and aesthetically eclectic.

Imge Ozcan

COLE, TEJU - OPEN CITY (RANDOM HOUSE, 2011)

‘Open City’ provides a first-person narrative of a young Nigerian man living in New York while completing a psychiatry residency. Sparse on plot, the novel is primarily concerned with the interiority of the narrator.

Solitary, discerning, and apolitical, Julius traverses the streets of New York (and during a brief interlude, Brussels) over the course of a year, providing varied musings on history, art, and the cityscape itself, while learning the life stories of individuals, often unmoored by dislocation, from across the socioeconomic spectrum.

It is these encounters that provide the most fascinating sections of the novel, providing evocative vignettes of immigrant life that leave a lasting impression, aided by the non-judgemental, impartial approach that Julius explicitly borrows from his psychiatry practice. One such encounter with a disillusioned young Moroccan man in Brussels with thwarted dreams of becoming a post-colonial intellectual is particularly trenchant.

Nonetheless, the narrator’s detached cosmopolitanism creates a gulf between himself and others, allowing him to sympathize in the abstract with the plight of many of those he encounters while leaving him unable to empathize with the lived experiences of others. While he often expresses guilt about this lack of genuine, transformative connection, it is fleeting and evanescent, and one wonders if this guilt is driven more by his ideological obligations than any genuine feeling.

What becomes implicit during the course of his varied encounters and associated ruminations is that the impartiality and liberality by which he views the world belies unacknowledged moral and ethical commitments that he refuses to interrogate lest it puncture the surety of his self-image. This perhaps explains the startling revelations about the narrator's past that make up the novel’s climax.

All in all, ‘Open City’ is an excellent novel that subtly interrogates what it means to be a ‘cosmopolitan’ in the 21st century.

Pradeepan Sarma

DESPRET, VINCIANE - HABITER EN OISEAU (ACTES SUD, 2019)

‘Inhabiting a territory’ is crucial, since life itself is dependent on relations we establish with our environments and the others that are a part of it. In this marvellously written book, Vinciane Despret dives into the world of birds and ornithology in order to try to grasp what a territory might be from the point of view of the birds.

When, why and how do they sing? Why and where do they parade? When and how do they chase away each other or not? When do they do it for the show? Where do they build their nests? Do they depend from the territories’ resources? And so on. Tons of studies and interpretations are contained in Despret’s subtle and generous text. Everything is in the details. The more we read, the more we understand that a territory is a very complex network of relations and significations (which can certainly not be translated into Property or Sovereignty). And no, we should not extrapolate from birds to ourselves. But what we can learn is that we must be very careful and nuanced when we observe and depict birds as they dance, parade, whistle and sing. At least with regards to territories, they are certainly more complex to understand than states, real estate brokers and other flag-planters.

Slow science is the best.

Please surf to this video, it’s not Vinciane Despret’s book, but Mr. E’s ‘I like birds’.

I don’t know why, but I feel why.

Serge Gutwirth

FIRESTONE, JENNIFER - TEN (BLAZEVOX, 2018)

A small booklet of one-pager poems, part of a delicately woven fabric of language on the cusp of suffering and surprise, wanting and wonder. I found it in one of the most delicious bookshops ever, Trident Book Sellers and Café, in Boulder, Colorado. They also started Trident Press, publishing “punk rock travelogues, occult spiritual texts, weirdo fiction, anarchist political philosophy, and vertiginous poetry, among others. However, the releases from Trident Press are more alike than they are different”. Great coffee. Great company (a nicely polysemous concept).

‘Ten’ is written from the perspective of pain, of being wounded, being treated, of post-operational recovery. The poetry is light and white, it remains on the surface of things because that already provides abundance. In the interstices of the poetry, the author presents diary-like intermezzos by way of prose, addressing herself as ‘you’. Each page contains 10 lines of poetry, the number of perfection; addressed from the existential anxiety of different types of pain, the uncertainty they impose and the fragility they invoke.

Mireille Hildebrandt

GROSSI, PAOLO - THE WORLD OF COLLECTIVE LANDS [IL MONDO DELLE TERRE COLLETTIVE] (QUODLIBET, 2019)

With this book the historian of law and former President of the Italian Constitutional Court Paolo Grossi invites jurists to rediscover all the complexity of the legal landscape. “(...) In the early 1950s, the idea of the State as the only source of law through its Codes had eventually become prominent in the common sense. From the ancient Romans to the modern State, the legal universe had been characterized by pluralism and multiplicity; by a legal science participated by judges, notaries and lawyers; by customary norms and daily practices left free in their vitality (...). This was now all reduced into a bunch of norms that were conceived far away from the social chaos they were supposed to regulate” (pp. 19-20). This happened at the expense of local communities whose life was organised around ‘communal property’ of land. In modern times we have become accustomed to believing that individual property is the best and only possible organization of economic and social facts. The 20th century has tried to eliminate communal properties as an ‘alternative’ form of organisation and as source of normativity, despite them always having been present in Europe, and despite populations having constantly defended them. Today, following a doctrinal debate that has lasted more than a century, these land set-ups are regaining legitimacy. In a law of 2017, the Italian legal system recognises them as ‘primary source of law’ and grants them constitutional protection, not least because of their contribution to ecological regeneration, socio-economic integration and territorial conservation.

The book contains many messages. The one I prefer is that (legal) life can be re-instilled into realities that seem condemned to extinction, if only jurists accept the task of bringing into the debates in which they participate the voice of the many alternatives that inhabit a (re)complex(ified) legal world.

Alessia Tanas

HONEYMAN, GAIL - ELEANOR OLIPHANT IS COMPLETELY FINE (HARPER COLLINS, 2017)

While stranded in an airport in a desert, I picked up this novel in a bookshop and nearly read it all while waiting for my plane, since it was so captivating. The novel follows a woman, Eleanor, who, as the title states, is completely fine according to her self-assessment. As the novel progresses, the reader slowly realises (and so does Eleanor) that some things that she was accepting are actually not that fine. Through this journey the novel takes the reader from very funny aspects of the human psyche to its darkest corners, illustrating that humans are communal beings, to a certain extent dependent on social connections. The novel also covers the difference between solitude and loneliness and shows how a little kindness can often go a long way.

I can only warmly recommend this book to anybody who wants to be reminded about the goodness in our world.

Laura Drechsler

Editors

LSTS books of the year 2019 was edited by Dariusz Kloza, Gloria González Fuster, Laura Drechsler and Laurence Diver.

Note by the editors: Accompanying pictures are included for illustration purposes, and might or might not correspond to the cover of the edition the reviewer actually read.

IGO, SARAH E. - THE AVERAGED AMERICAN: SURVEYS, CITIZENS, AND THE MAKING OF A MASS PUBLIC (HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2007)

I hate science fiction. Actually, not all science fiction, but most of it. To be fair, I also hate historical fictions. And fiction books in general, with some exceptions of course. This does not mean, however, that I am particularly fond of reality. It depends. Anyway, this year I spent quite a lot of time recommending some history books, like Josh Lauer’s ‘Creditworthy: A History of Consumer Surveillance and Financial Identity in America’ (Columbia University Press, 2017), or Jessica Lake’s ‘The Face That Launched a Thousand Lawsuits: The American Women who Forged a Right to Privacy’ (Yale University Press, 2016).

Sarah E. Igo is an American professor of History, Law, Political Science, and Sociology, and has a Chair in American History. She has notably published ‘The Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in Modern America’ (Harvard University Press, 2018). ‘The Averaged American’, her first book, focuses on the advent of surveys and opinion polls, more specifically on their search of the ‘average American’ (their attempt at ‘profiling the mainstream’, as Igo puts it), and is full of interesting reflections on what happens to a society when it is pushed to learn about itself by disclosing itself to itself. Igo’s writing might occasionally sound a bit lost in detail, but it does manage to put forward important insights on the role of mass media and scientific (and non-scientific) methods in constructing publics, masses and the individuals behind them, and on the notions of representation, underrepresentation and representativeness, as well as, more generally, on the political and fictional nature of normality.

Recommended.

Gloria González Fuster

JUDT, TONY - ILL FARES THE LAND (PENGUIN, 2010)VAN BAVEL, BAS - THE INVISIBLE HAND? HOW MARKET ECONOMIES HAVE EMERGED AND DECLINED SINCE AD 500 (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2016)WARD, JESMYN - SALVAGE THE BONES (BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING, 2011)MICHIELS, IVO - HET BOEK ALFA (DE BEZIGE BIJ, 1963)

I read and re-read more political theory these days to overcome constant overexposure to partial theories and outlooks that surround me. The rise of the right in Belgium and other European states does not surprise me in the light of the discursive impotence of the centre and other spectra to address major societal concerns about change. The demands of the yellow jacket movement in their quest for more social justice do not require that much intellectual effort of the political and intellectual elites, but require modesty and perseverance in developing a long-term policy to regain their trust. Trust in our system of taxation and social services, trust in our commitment to end inequality, trust in our belief that all citizens, yellow jacket or not, have a sense of dignity and would rather not block the streets to demand for self-evident things.

A bit more challenging and more prone to lack of political understanding are the demands of farmers. Are those farmers blocking Dutch traffic sitting on their enormous vehicles overheated traditionalists, rejecting all change in farming methods needed in the name of climate change policies? Can we safely assume that the farmers who have implemented change are working on their fields and not demonstrating? Is the problem one within this sector? Why living up to societal demands to change in a context where demands are systematically neglected? Is there a social contract with regard to farming in our countries or is the mantra they have to abide to something like ‘there is no more place for European farming in a global economy’ or ‘start farming organic now if you want to survive’?. A climate friendly food strategy will not work if we leave these questions only to the economic masterminds that are pushing the wheels of European and the global economy. William Beveridge’s 1942 observation that political philosophy had been obscured in public debates by economic thinking still holds true, and a re-reading of Tony Judt is one way to explore a rich range of alternative perspectives.

A powerful source of obscurity is this construct of the European Union. Years of admiration for the project of European integration and the idea of achieving an “ever closer union among the peoples of Europe” are slowly losing their imprint. Bas van Bavel’s historical account of new market elites contains poisonous remarks about the role the European Union today – that wherever they emerge (Iraq in the early Middle Ages, Italy six centuries ago, the Netherlands five centuries ago and Britain three centuries ago), they translate economic wealth into political leverage, and abuse the political system to further their power position causing market decline. Van Bavel’s lack of nuance about the role of the EU as a tool to consolidate economic power of some elites in ‘The Invisible Hand? How market economies have emerged and declined since AD 500’ has profoundly disturbed me, coming from an historian immersed in factual accounts about the rise and decline of systems (as opposed to EU criticisms coming from traditional left-wing voices). Perhaps van Bavel’s impact on me is so strong because unveiling the real function of the EU is far from the central theme in the book. The diagnosis is made in passing.

More intellectual effort is needed to address fears about immigration (and the role of the European Union, for instance in imposing quotas). “There is quite a lot of evidence that people trust other people more if they have a lot in common with them” (Judt, p. 66). A growing familiarity with other European countries explains the relative contemporary sense of being ‘European’. The European identity is there complementing other identities. The EU citizenship identity is however fragile and can be dismantled. Concerns about borders being too open, loss of ethnic homogeneity and influx of less educated populations should not be disqualified as extreme right white noise. Overseeing the importance of social cohesion for the twentieth century welfare state should invite a broader part of the polity to step in. ‘Nothing can be done about immigration’, is a no go, an insult to politics and political theory. It is impressive to see how a political theorist like Tony Judt only needs a couple pages to lay out the problem(s). “A steady increase in the number of immigrants, particularly immigrants from the ‘third world’ correlates (…) with a noticeable decline in social cohesion. To put it bluntly, the Dutch and the English don’t much care to share their welfare states with their former colonial subjects from Indonesia, Surinam, Pakistan or Uganda; meanwhile Danes, like Austrians, resent ‘paying for’ the Muslim refugees who have flocked to their countries in the past years’ (p. 70).

The second problem addressed in the latter part of this quote is of a historical nature: not all European countries share the same past and rolling out one solution for the full Union is therefore much easier said than done. Less infantile reactions to calls from citizens from where-ever in Europe for more national sovereignty would have avoided the cultural war that is now taking place. This war is most explicit in the systematic flagellation of Eastern European countries like Hungary (see Furedi’s 2017 defence of Hungary in ‘Populism and the European Culture Wars’, Routledge).

In my reading of novels, I continue reading books suggested by my close friend Serge Gutwirth. Through him I discovered and admired the work of Jesmyn Ward, in particular ‘Salvage the Bones’ (2011) where a young black girl, faced with an unforeseen pregnancy in a poor and deprived context, teaches us that freedom not necessarily resides in what we are, but in what we think we are.

I am also exploring the literary canon project of the Royal Academy for Dutch Language and Literature and the Flemish Literature Fund offering no less than fifty essential works in Dutch (full text). ‘Refrains’ (1528) by Anna Bijns and ‘Het boek alfa’ (1963) by Ivo Michiels have been digested. 48 books to go.

I am well aware of the political discussions and cultural wars around literary canons. That is why I am enjoying this so much. Politics is serious fun.

Paul De Hert

KAUL PADTE, RICHA - CYBER SEXY: RETHINKING PORNOGRAPHY (PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE, 2018)

In her debut non-fiction book, Richa Kaul Padte approaches the discussion around sexual content with an intriguing and inimitable honesty, based on carefully selected references to culture, history, society and law, as well as personal experiences of hers and her interviewees. Her stimulus goes back in 2013, when a petition filed to the Supreme Court of India called for a complete ban on pornography, blaming the latter more or less “for all of society’s evils”. Few months later, Padte responded with an article entitled ‘Of Porn, Morality and Censorship: A Perspective from India’, while at the same time she started extensive research on the topic.

Padte argues that, from the sexual drawings on the Pompeii walls to the newest digital avenues enabling the establishment and dissemination of online sex cultures, porn has always been a societal and individual driver, dependent upon continuously evolving power structures, wars among ‘values’ and relevant (or not) demarcations. Chatrooms, fan fiction, apps, video games, homemade or studio porn, animation, sex tech and art: she takes a look at everything, through the lenses of technology, ‘mass intimacy’, privacy and consent.

Pornography, like privacy, does not have a commonly-agreed definition. And yet, as the American Judge Potter Stewart supposedly said in the 1960s, even if “I can’t define pornography, (…) I know it when I see it”. One thing is certain – as suggested in the preface: “This book is going to make a great conversation starter. Or ender”.

Olga Gkotsopoulou

MAGEE, BRYAN - ULTIMATE QUESTIONS (PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2017)

Magee, who unfortunately died this year, would like to be known as the ‘Great Agnostic’. ‘Ultimate Questions’ is his short, beautifully written encapsulation of that philosophy. Although many a great philosopher could undoubtedly be referenced in the domains of scepticism, empiricism, and phenomenology, with the exception of Wittgenstein Magee deliberately declines to do so, aiming instead to draw the reader in to the basic story of being and experience, and to help her (re)connect with the wonder of existence and the majesty of it all. These are fundamental, indeed ultimate, questions that stand apart from the cloying grasp of performative intellectualism, and as such Magee illuminates his perspective in crystalline, perhaps slightly melancholic prose that brings to mind an after-dinner discussion with a wise uncle more than it does the university lecture hall.

Among many other things Magee was a populariser of philosophy, producing a series of BBC interviews in the 1970s-80s in which he discussed with various notable philosophers their own work and the work of the greats who preceded them. He clearly valued, and was extremely adept at, articulating complex ideas in intelligible ways – ‘Ultimate Questions’ is a perfect example, being simultaneously accessible and utterly precise (in linguistic expression, if not always in his conclusions). More philosophers, at least when wearing their philosopher’s hat, should aim to write like this.

Laurence Diver

MAGRITTE, RENÉ - SELECTED WRITINGS (ALMA BOOKS, 2018; EDITED BY KATHLEEN ROONEY AND ERIC PLATTNER, TRANSLATED BY JO LEVY)

This farewell gift became my bus 95 companion during the first months of 2019. When the bus would not show up or a new ‘detour’ would add an extra half an hour to my ride, Magritte would always remind me that “the banality common to all things, that’s the mystery”. As its title suggests, it is a ‘selection’ – not a ‘collection’ – of Magritte’s writings, for the first time translated in English, based on the original compilation put together by Andre Blavier (Magritte, René, Écrits complets. Paris: Flammarion 1979), further enhanced and thoughtfully revised. The selection has a long yet unknown history with respect to its conception and materialization, dating back to the early 1980s.

Aiming to create the ‘portrait of a mind’, the writings are grouped chronologically and include essays, poems, prose, manifestos, interviews, comments, replies, unpublished texts, homages, reviews, film plots, postcards, sketches, dialogues, memoirs, autobiographical briefs, letters, aphorisms, posters, wordplays and images. Every page contributes to the mapping of Magritte’s artistic evolution explained in his own words, revealing deep sympathies and profound dislikes as well as his relation to prominent figures, such as Freud, Breton, Éluard, Duchamp, Ernst, Dali, de Chirico, Goemans, Colinet, Poe and many more.

The underlying tone is given by Magritte himself: “The point is a new vision, where the viewer rediscovers his isolation and hears the silence of the world. Neither modest nor proud, I’ve done what I thought I had to do”.

Olga Gkotsopoulou

MALGIERI, EMANUELA - ETERNAMENTETUA (ALBATROS, 2019)

‘Eternamentetua’ describes the story of Rita, my grandmother, a Neapolitan woman born in 1926. The author, an archaeologist and the granddaughter of Rita, rebuilds the story of Naples in the first half of century – from emigration stories of her parents to the fascist era to World War II scenarios – through the particular life of the protagonist. The author accidentally found the love letters that Rita exchanged with Roberto, her future husband (my grandfather), between 1944 and 1951. Those letters had been kept secret by my mother during the last two decades, but the depth of feelings and historical events described in those letters needed to be shared with a bigger audience.

The story of Rita is not just the story of renaissance from war destruction in Southern Italy, but it is also the story of a changing society: the slow move from patriarchy to gender parity, the difficult relationship between Rita and her father, the ‘illegitimate’ love of her father with a young woman, who delivered an ‘illegitimate’ child who was adopted by Rita’s mother to avoid any scandal. In sum: not just Elena Ferrante can describe the intensity of post-war scenarios in Italy.

Gianclaudio Malgieri

MCEWAN, IAN - MACHINES LIKE ME (JONATHAN CAPE, 2019)

The latest work of Ian McEwan is so relevant for all technology-and-society researchers (or even just curious people or nerds). In a dystopian UK of 1981 (where the Beatles are still working and Margaret Thatcher is much stronger than ever), a young man spends all his fortune to buy the best android on the market. Taking care of this robot, better than any Alexa or Siri, means taking care of a new born ‘human’ life, and this is the occasion for a personal development of the protagonist and of his love towards her neighbour. ‘Machines like me’ describes a machine that slowly takes the personality of the protagonist. Where does the machine begin and the human learner end?

The book is extremely brave, since it explores the philosophical challenge of post-humanism in a (dystopian) pre-digital era. This paradox makes even stronger the contradictions of post-human life issues and the relationship between ‘I’, ‘me’ and the ‘self’.

Gianclaudio Malgieri

MEYER, ERIN - THE CULTURE MAP: DECODING HOW PEOPLE THINK, LEAD, AND GET THINGS DONE ACROSS CULTURES (PUBLICAFFAIRS, 2014)

Meyer’s book is an excellent guide to various cultures we encounter in an international (work) environment. The book not only categorizes cultures based on different perspectives (e.g. depth of the context of communication, punctuality, provision and acceptance of critiques, etc.) but gives the reader suggestions how to identify such cultural differences and how to address them. Knowing, for example, that a message should be written differently to a Dutch than a Spanish colleague can make a difference not only in personal relations, but in work environment as well. A face-to-face meeting with an Italian or with a German colleague requires different attitude, starts in various times (regardless of what has been scheduled) and flows in different ways. No need to describe the efficiency of such meeting when the German colleague is approached in an Italian way or vice versa.

Countless time is spent on negotiating with external and internal colleagues, leading to a permanent tension. Such stress is a result of ignorance towards cultural differences. Adapting to others’ culture does not require particular effort but can affect one’s mood and thus undermine the efficiency of work significantly.

Therefore, this book should be a mandatory reading for everyone who enters to and operates in an international community. With such guidance and a small attention, the effectiveness in communication could be noticeably increased, leading indirectly to the reduction of stress as well. Which is of utmost importance for all of us.

István Böröcz

MEYER, ERIN - THE CULTURE MAP: DECODING HOW PEOPLE THINK, LEAD, AND GET THINGS DONE ACROSS CULTURES (PUBLICAFFAIRS, 2014)

The must-read book for everyone who works and communicates with people from different countries. Erin Meyer created a whole system to describe where and how much your culture defines how direct you are, your expressiveness, how you structure your work, manage the time, make decisions, build relationship with the boss and other colleagues, the way you disagree and the level of your trust. For all the mentioned elements the authors created measure scales where countries are placed in different positions. Besides the very clear structure of the culture differences, Meyer supports every feature with explanatory and vivid examples. “Cultural patterns of behavior and belief frequently impact our perceptions (what we see), cognitions (what we think), and actions (what we do).”

This book helps us to decode these cultural patterns, distinguish them from personal characteristics and it explains how to deal and efficiently work with people from different countries. Moreover, the book helps to understand your own features that are rooted in your culture rather than in your personality.

Anastasiya Kiseleva

SHAKESPEARE, WILLIAM - THE TRAGEDY OF MACBETH (1606)

This was a ‘Macbeth’ year in Belgium, as it appeared four times on four different stages. Two theatres in Brussels showed it, each with their own modern touch on the play: Théâtre Royal du Parc (February) and Varia (April). Next, Opera Vlaanderen in Antwerp showed Verdi’s interpretation (June) and La Monnaie / De Munt in Brussels – Dusapin’s take as ‘Macbeth Underworld’ (September). I’ve seen them all and this gave me a chance to re-visit the play.

In high school, I found ‘Macbeth’ much more impressive than ‘Hamlet’. ‘Macbeth’ tells a story about power and madness, but also about many other things, personalities and places – Shakespeare was always timeless and versatile. But it’s also a play about the future, destiny and prophecies. Those who work on the concept of ‘risk’ and the like could easily relate their work to the Scottish play.

Dariusz Kloza

SHAPIRO, ALAN - AGAINST TRANSLATION (CHICAGO UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2019)

This thin volume of exquisite prose was discovered in Berkeley’s University Press Books on Bancroft Way, one these places where extra-ordinary publications (both new and second hand) delight you into buying what you did not know you longed for, moving next door to the seminal Musical Offering Café (with which the bookshop shares a toilet). To sip excellent coffee (or wine), listen to ‘classical’ music and move straight into the book that will thus allow you to procrastinate (often inducing highly relevant new insights you would never have encountered when only finding what you were looking for).

The title called out to you, as you were in the middle of a delightful workshop at the Simons Institute of Theoretical Computer Science, on the topic of ‘Beyond Differential Privacy’. Some of the participants treated you to some hostile questionings that opened your eyes to computer scientists’ urge to formalize and solve whatever is presented as a problem. As you are not against formalisation or problem solving, you were a bit surprised by the surge of misunderstandings that erupted in response to your presentation. Your understanding of formalisation is that it requires a translation that is also a disambiguation, thus losing polysemy while gaining a specific type of certainty. Your problem starts where some seem to assume that such loss must be denied or swept under the carpet, to make room for supposedly desirable operations in real life settings that are enabled by the formalization. Anyhow, your mood surged when you saw the title – a tribute (if not an ode) to singularity: no, words cannot grasp the meaning they generate; no, we don’t understand another’s pain or suffering; no, kindness does have limits. You are an optimist, so you are not at all against translation – but the content soothed your soul, nevertheless. Formalisation has its limits, if not heeded it may break the fabric of our shared world.

Savour ‘Against Translation’, especially when you engage in translation.

Mireille Hildebrandt

SNOWDON, EDWARD - PERMANENT RECORD (METROPOLITAN BOOKS, 2019)

The reason to list this book is simple: we all think we know everything about him and his story, but the book reveals so much more. And it reminds everyone of what privacy means in the Digital Age.

Juraj Sajfert

STANLEY ROBINSON, KIM - THE COMPLETE MARS TRILOGY: RED MARS, GREEN MARS & BLUE MARS (HARPER VOYAGER, 2018)

Written in the early nineties by the still prolific Kim Stanley Robinson (recent novels: New York 2140 (2017) and Red Moon (2019)), the Mars trilogy is an extremely elaborated story of Mars’ colonization by humans. It starts in the 2026 with the arrival of the first hundred (actually, they are 101, because there is a clandestino on board, the mysterious Kropotkinian rasta-anarchist named Coyote, indeed my favorite character in the novel) on the cold and inhospitable planet and it ends in almost 200 years later, when the Martians start to further explore the planetary system and beyond. During this period Earth is facing still growing problems, not only because of the brusque melting of Antarctica and drastic climate issues, but also as a result of the further subjugation and erosion of state power by still more potent transnational and bold corporations.

The trilogy is immensely rich. The many characters have intriguing and surprising personalities and they all have talents and represent the scientific knowledge and know-hows necessary to turn Mars into a livable and attractive planet. Everything seems realistic, possible and explainable. They invent Martian politics and fractions are formed around issues such as the relations to earth, the limits of terraforming and the preservation of the planet, the way a Mars government should be formed, or not. Martian revolts take place. Tensions grow when Earth and its Transnational Corporations start to move people to Mars to do away with overpopulation. New generations of Martian born humans turn effectively into Martians, a new people with physical differences, linked to other atmospheric conditions. Genetic manipulations become common. All kind of plots - from love affairs to crime and political struggles- cross the trilogy, which are very intelligently and unexpectedly unveiled. Openings are made towards further colonization of the planetary system (which the author develops in another great novel: the more recent 2312).The author conceives all kind of imaginary devices (the fantastic space elevators!) and ways of doing which are always plausible, and as a reader, do just not stop to intrigue you. And finally, it is a very refreshing and hope-generating book, especially because a constitutional system seems to be developed wherein the many settlements or commons can autonomously function and network.

Additionally, it is clear that Kim Stanley Robinson knows precisely what’s happening today in many sciences, in technology and innovation, in STS, in linguistics, in politics and economy, and he formulates ideas and views, which can be learned from. He shows the force of telling stories, which are always locally and ecologically embedded. No principled, abstract and generalizing analytical groundings or objectives, but questioning situations demanding the construction of their own prudent and forward looking solutions. He is a master in speculative narration and in the art of consequences.

I have spent half a summer with the trilogy. It felt so good that I spent the other half with Robinson’s Earth trilogy called "Science in the capital". And there are still many Robinson books to drift away with.

Serge Gutwirth

SULLIVAN, HANNAH - THREE POEMS (FABER & FABER, 2018)

Do you love simple titles, or don’t you? A title that refuses to summarise, indicate, appetise or even imagine. You did not find this. It found you, sent by a dear colleague and friend for your birthday, that joyful reminder of growth and decay. So, Sullivan (Professor of English at New College, Oxford) wrote three poems. They treat the reader to a steady stream of consciousness, situated, abstract, on the spot, strangely aligned and alienated.

What will survive of me?Larkin though the answer might be ‘love’,But couldn’t prove it.

You love that (poem 3.31; they are numbered instead of titled). You love that, because what matters might resist proof. And will require vigilance, if not engagement. Part of the stream of verse addresses a person called ‘you’ (same as in ‘Ten’, see above or below). You who is I. You love that too. It acknowledges the cogitas (ergo sum). It irritates the reader, maybe, at first. But once the change of perspective dawns, it becomes even more interesting than what is written from the ‘I’. There is a productive disconnection here that tinges what is voiced, as if the privileged access we assume to our own experience collapses while being exhibited. I will stop now – poetry should not be explained. As Rutger Kopland said after being asked what he meant with a specific poem: “if I had found a better way of expressing that meaning I would not have written this poem”.

Mireille Hildebrandt

TAYLOR, ELIZABETH - A VIEW OF THE HARBOUR (ALFRED A. KNOPF, 1947; RE-PUBLISHED BY VIRAGO PRESS, 2018)

This quiet yet intriguing novel by Elizabeth Taylor (not the actress) stayed with me long after I finished it. The novel describes the life of several inhabitants of a tiny English harbour town right after the second world war. The story is mainly driven by observations the characters make about each other either in conversations, but also via ‘surveillance’ by watching them through windows, doors etc. With this way of story-telling the author captures beautifully the advantages and disadvantages of living in a small community, where everybody knows everybody and how this limitation on privacy affects individual life choices.

My edition of the novel also included interesting facts about Elizabeth Taylor herself, explaining that while she was quite a productive author (12 books and many short stories), she never gained much recognition during her lifetime beyond a small circle of experts (also because she shared her name with another person that did become quite famous – the actress). I hope this changes now with this republication since she was really a superb story-teller.

Laura Drechsler

TOKARCZUK, OLGA - FLIGHTS [BIEGUNI] (FITZCARRALDO, 2017; TRANSLATED BY JENNIFER CROFT)

‘Flights’ is a novel by Olga Tokarczuk, 2018’s Nobel literature prize winner. The way this novel is structured is unique and a pleasure to read: the reader jumps between thoughts of someone (presumably the author) on travelling and growing up in Poland, and several short stories (some of them only one paragraph) relating to travelling to both the outside world and the inside of humans (human autonomy plays a key role in this novel). They way all these stories and thoughts are intertwined resembles one’s experience on a journey, where one impression hunts the next one and because of all the intensity they seem completely disconnected. The novel also covers all the emotions that journeys include, from love to joy to panic to grief.

It’s a book to re-read before travelling or to just randomly open at a page for some deep insights for whatever problem one struggles with. I cannot wait to read more of this fantastic author (and wish I could read Polish to understand the originals, though the translation for this book was excellent).

Laura Drechsler

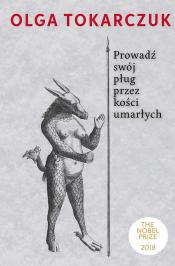

TOKARCZUK, OLGA - PROWADŹ SWÓJ PŁUG PRZEZ KOŚCI UMARŁYCH [DRIVE YOUR PLOW OVER THE BONES OF THE DEAD] (WYDAWNICTWO LITERACKIE, 2009)

A surreal, subtly humorous novel, in which justice is sought for animal beings hunted by human beings, merely for sport, as these animal beings rather cannot seek it for themselves. A novel on many aspects of contemporary politics, in which Tokarczuk – winner of the (delayed) 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature (as well as of many other literary awards earlier) – takes a pro-environment and pro-animal rights stance.

This aspect reminded me of some influential (academic) writings on environmentalism, especially Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ (1962), Christopher Stone’s ‘Should Trees Have Standing?’ (1972) or David Gee’s edited report ‘Late lessons from early warnings’ (2001/2013). (I saw this story for the first time on the stage of Teatr Polski in Poznań in 2010 as ‘Pomórnik. Kryminał ekologiczny’ [Cryptid. An eco-detective novel] by Emilia Sadowska. Next, in 2017, I saw it on a silver screen, as ‘Pokot’ [Spoor] by Agnieszka Holland.)

Dariusz Kloza

VIECELI, ALBERTO - HOLDING THE CAMERA (SPECTOR BOOKS, 2019)

Instruction manuals can be a nuisance: you never know whether to throw them away directly, or put them in a special place in case you might need them someday, knowing that the day you might actually need them it will be impossible to remember where you put them. This applies to standard instruction manuals. Some, of course, are different. I once bought online a second-hand Canon AE-1 Program camera which was delivered with its original manual, and I found it so nice that I read not once but twice, and then placed it on my shelf of very important things. It thus came as no surprise to me that somebody was collecting manuals of old film cameras, both physically and digitally.

Alberto Vieceli amassed thousands, and ‘Holding The Camera’ presents a selection of pictures from these manuals specifically dealing with the question of how to hold the camera. There are many smart things that could be said about these images, and, conveniently, a number of them are written by Nadine Olonetsky in an accompanying essay, which quotes Vilém Flusser and evokes many layers of interpretation for these intertwined gestures, gazes, and apparatuses. But there is still much more to be discovered here: these images are actually peculiarly rich because they represent both an ideal action (‘this is the best way to hold this camera’) and an ideal image of an imagined audience (‘this is how we imagine that the kind of people to whom we are selling our cameras might like to imagine them holding it’). They are also peculiar because they are part of a world where you couldn’t just write down ‘you may hold the camera vertically, or horizontally’, but you had to illustrate this (‘see, here, a person holding the camera vertically’, ‘see, here, the same person holding the same camera horizontally’), or maybe you did not really have to illustrate this, but for some reason everybody did.

Why? Who started this? And who stopped it? Was it ever useful? And what happens when you hold the camera diagonally? There are still so many questions to be asked, all hidden here, in this beautiful book, which also features, of course, a great number of wonderful old cameras, as well as so much inspiration as to how to hold them naturally.

Gloria González Fuster