Books (and more) of the year 2021

Every year, the members of the Law, Science, Technology and Society (LSTS) Research Group of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) are invited to reflect on the books that have influenced the most their (academic) lives and/or have been inspirational. This year we expanded the call to include also films, exhibitions, records, podcasts, TV/platform series, plays, concerts, or any similar cultural artifact or event that has impacted our (academic) life in 2021.

As per tradition, here are our best of 2021. The views expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the views of LSTS as a group.

See the following links for the editions of 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017 and 2016.

James Blake - Friends that break your heart (2021 Republic) (record)

I have not always been the greatest fan of James Blake. But then it happened. I started to become punctually obsessed with some of his songs, and this year when I learned ‘Friends that break your heart’ was published I immediately ordered the vinyl, and impatiently waited for it. Totally worthwhile agitation. It is a great record, full of songs worth being obsessed with – let me mention ‘Lost Angel Nights’ or ‘Famous last words’. My favourite, however, is ‘Say what you will’. The official video portrays the artist as a loser in constant comparison with another artist (Finneas, played by Finneas), delivering a message that must surely in a way or another resonate with all academics, in this academic world in which we are all constantly reminded that others are publishing more, faster, and better, ranking higher, thinking deeper, looking smarter, and getting more likes and funds, in no particular order. The lyrics are wonderful, and include the memorable passage ‘I might not make all those psychopaths proud, at least I can see the faces of the smaller crowds’. As Blake sweetly explains in this 2020 live #StayHome video, ‘Say what you will’ is a song ‘about being OK with the place you are at’, and ‘just generally saying fuck’em all’. A too often underrated state of mind.

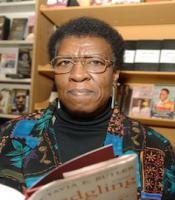

Octavia Butler and Ursula Le Guin - Feminist science fiction classics

A fan of science fiction, and somewhat embarrassed by the realization that I had never read any of the classics of feminist science fiction, I undertook a journey through the works of Octavia Butler and Ursula Le Guin.

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Talents and Parable of the Sower stood out for their clarity of language and honesty about the human condition and political reality, touching on racism, slavery, climate change, capitalism and religion. Not the easiest books to stomach, but very rewarding none the less. The books offer dystopian coming of age story of a black woman and ultimate leader of a new religion called Earthseed, central beliefs of which include that “God is Change” and that it’s humanity’s ultimate destiny to inhabit other planets. The books were written in the 1990s and situated in the 2020s and later. The many similarities are striking indeed.

From Ursula Le Guin, I would make special mention of the Earthsea cycle, which tells a story of wizards, dragons, and a veritable school for wizardry, while touching on gender, intercultural dynamics and more. The first three books were written around the year 1970, while the later ones were written much later in 1990 and 2001. What makes this interesting is that the feminist perspectives informing the book are changing as well. The later books, which depart somewhat from the young adult genre of the first three, explore certain problematic aspects of the world introduced by the first books, such as why women can’t be wizards in Earthsea and particular characteristics of male and female power. The Taoist influence on Le Guin is very notable in the Earthsea series as well.

Caroline Criado Perez - Invisible Women (Penguin Random House UK 2019)

The thickness of this book took me by surprise. I wondered: is there really so much to say about Invisible Women and data bias? Surely there is, and after I finished reading the book, I believe many more books with similarly illuminating stories and research could be and should be written.

This book left a deep impression on me. It showed me that my understanding of gender issues has been shaped by my upbringing and the societies in which I’ve lived. I recommend this illuminating and at the same time utterly depressing book to everyone who is open to the opportunities of a brighter, more diverse and inclusive future.

Many examples described in the book, ranging from the lighting of parks, medicine production and car safety to disaster response, leadership and politics, shocked me because they concerned ‘design decisions’ that were data-biased. The example that struck me the most and got me hooked was the one concerning snow clearing described in the first chapter.

Can snow clearing be sexist? Can it favour men or women? Coming from Lithuania, where it snows every winter and everyone deals with it just fine, my initial answer was: no, of course not. It’s an environmental issue. It is just snow clearing. You pick up the shovel and clear snow from your path, backyard or a pond if you are up for ice skating. All the important places are made accessible by the relentless efforts of the workers of municipal maintenance companies.

The author showed me how wrong I was in my answer! I did not see the bigger picture. I had what the author describes as: ‘a gap in perspective’. The analysis of several factors (cost of medical treatments and loss of productivity) in several places in Sweden clearly shows that things change depending on which areas get cleared of snow first. This example also demonstrates how even a simple decision made about what to clear first – streets, sidewalks or bike paths – can unintentionally discriminate against a large part of society. In the end, no data is neutral, and its reading is rarely going to lead us to the right (beneficial and inclusive) decisions if we read it blindly.

WITOLD GOMBROWICZ - Trans-Atlantyk (An Alternative translation) (translated by Danuta Borchardt, Yale University Press 2014)

The book is loosely based around the real-life history of the author, Witold Gombrowicz, a Polish writer who got stuck in Argentina after WW2 broke out. I’ve received it as a gift from a Polish friend who thought that it was suitable for me: an Argentinian, grandson of a Pole, who got stuck on the other side of Atlantic because of a worldwide disaster, in this case COVID-19.

The initial chapters, where Gombrowicz arrives at Buenos Aires, almost felt like the descriptions my grandparents made about the early 20th century Buenos Aires: a city in which European immigrants found a second opportunity to grow with enormous potential. Immediately after landing there, Germany invaded Poland and Gombrowicz found himself doubting what to do: stay there in Argentina or find a way to return to Europe and his motherland. As somebody who arrived in a new country just 3 months before COVID hit the world, I could not but relate to those feelings.

While complex because of the narrative style used by Gombrowicz (I admit that several paragraphs demanded a couple of readings), the book offers a lot to think about in relation to migration, but also the tension between an individual and his/her motherland in moments of crisis.

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff - The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (London: Allen Lane 2018)

This seminal book by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and lawyer Greg Lukianoff deals with the remarkable change of attitudes among college students in the US from 2014 onwards, i.e. since the arrival of Generation Z. Whereas students of the previous generations typically arrived at university with demands for greater freedom, the current generation seems to be demanding above all to be made feel "safe", especially from what is considered "harmful speech"; hence the increased demand for de-platforming of speakers and cancelling of professors who do not present views in line with current liberal (in the American sense) thinking. At the heart of this problem, according to Haidt and Lukianoff, lies the adoption by this generation of three "untruths", viz. "What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker", "Always trust your feelings", "Life is a battle between good people and bad people", i.e., the kind of tenets cognitive-behavioural therapists will try to dismantle in their clients (the authors also show how Generation Z reports an increase in mental health issues, particularly depression and anxiety). What led to this state of affairs? Haidt and Lukianoff blame, among various factors, the increased polarisation of American politics, paranoid parenting from the Nineties onwards, the lack of play, particularly in conjunction with the rise of social media (Generation Z is the first generation that does not remember a world without the internet).

While the authors recognised later that the phenomenon is not limited to the US (Haidt recently wrote that perhaps the title of the book should have been ‘The Coddling of the English-Speaking Mind’), they maintain that the situation in continental Europe (but not the UK…) seems to be different. I guess only time will tell?

Iris Origo - The Merchant of Prato: Francesco di Marco Datini, 1335–1410 (NYRB Classics 2020)

Although I would not place “The Merchant of Prato” under the life-changing or even deep-impact book category, reading it was an eye-opening experience for me. You see, I always suspected that our lives do not differ substantially from lives lived thousands of years ago (OK, I would start the count with Rome, not Greece), but I always wondered about the Middle Ages. At the time of Imperial Rome, Seneca’s writings dealt extensively with the matter of “busy lives”, therefore one can only imagine that (some people at least) were faced with time management issues similar to our own. But, the Middle Ages? How busy could one be in pre-Rennaisance, medieval Europe? Well, if I imagined times of parochial leisure, I could not have been more mistaken, it seems. Francesco Datini, the Merchant of Prato (whose statue and house in Prato are the latest additions to my bucket list), back in 1400 was every bit as busy and energetic as your next-door modern capitalist. He formed a holding company with subsidiaries all around Europe; he incorporated companies adopting Articles of Association of the type that we more or less use today; He dispersed risk as much as possible, to mitigate unstable politics; He was quick to cut his losses and the first to spot a new opportunity - internationally. He kept accounting books as complex as today’s, seldom paid his bills without a court order, constantly complained about taxes and tried to avoid them as best as possible. Once he became a local tycoon he invested heavily in his city so as to buy the good will of his co-patriots, but in vain. His relationship with his wife was complex.

Nevertheless what astonished me the most was his pace of work. All day long, for endless sleepless days in a row he would write letters to partners, colleagues, employees, friends, even to his wife - this is how we are able to reconstruct his life in such detail. I deeply sympathised with him; his daily routine does not seem that far away from mine, minus the pen and plus the keyboard.

At the end of the day the Merchant of Prato (that is otherwise a simple, but well-researched book) was a lesson in humility for me. Too often we consider that we live in exceptional times, that our lives are unprecedented, our problems and thoughts unique in the history of humanity. Apparently, nothing could be further from the truth: All that we feel and all that we live has been relived by millions before us. The Merchant of Prato would feel at ease riding on a plane (well, private jet) instead of horseback, using smartphones and online platforms to transact instead of paper, basically fearing the same things and living the same life as any one of us. The book’s greatest value, to me at least, is instructional, followed (closely) by informational.

PS: I read this book on Apple’s Books app, having bought it from Apple’s Book Store; I think that the Merchant of Prato would have appreciated the irony, me admiring Medieval capitalism and at the same time having paid good money to a trillion-dollar company merely for a license to read a book, that will be taken away from me if I ever decide to move away from its over-priced ecosystem. I suppose one’s only defence to such post-modern capitalism is to not really care.

Steven Levy - Facebook: The inside story (Blue Rider Press 2020)

This year made me discover the ‘technology’ section of my local library where I stumbled upon this book, which elaborates on the history of Facebook based on close access the writer got to Mark Zuckerberg via interviews. Initially sceptic of its value, I immediately got drawn into the description of the journey of Facebook from a small student network to the (META) mega-company it is today. The author does an amazing job describing all the choices that were made for Facebook to become what it is today and how often enough the consequences of these choices were only revealed years later. The coverage of the book sadly ends before much of the events of 2020 concerning Facebook occurred, but it still offers a very up to date overview of the business model that is still driving its decisions.

Craig Murphy and JoAnne Yates - Engineering Rules: Global Standard Setting Since 1880 (Johns Hopkins University Press Books 2019)

This is a great book for anyone who is interested in technical standardization. It provides the history of how and why standards were originally developed, and how they have evolved over the course of the years. The authors distinguish three waves of private standard setting, starting from the 19th century’s engineering standards to today’s corporate social responsibility and WebCrypto standards.

Kasuo Ishiguro - Klara and the Sun (London: Faber & Faber 2021)

I have devoured all of Ishiguro’s novels, and watched his zoom interview by fellow writer Alex Clark, streamed globally by The Guardian on 2 March 2020 about his new novel, before it was released. I loved the interview for the modesty, pensive reflection and obstinate responses given by Ishiguro, and I appreciate his taking the liberty to imagine what it would mean if ‘Artificial Intelligence’ or robotic agents were to gain some form of consciousness. His take differs substantially from Ian McEwan’s Machines like me, though one could cherry pick similarities. The main difference is that Ishiguro speaks for Klara, the ‘artificial’ carer-friend who was bought by a mother to provide company for and perhaps even to replace Josse, her young daughter who has serious health problems. By giving a voice to the inner thoughts and feelings of the artificial friend, Ishiguro crosses a line that McEwan did not cross, suggesting robots may indeed develop something akin to human agency, inviting the reader’s compassion for Klara and perhaps implying that such artificial agency should be recognised and respected.

In attributing human suffering, love and longing to an artificial agent, Ishiguro creates new ways of observing human interaction, showing the complexities of e.g. mother-daughter relationships from the vantage point of an outsider who is basically unseen – let’s say ‘cancelled’ – by the humans who use her to serve their own whims. We recognise the operations of sexism, racism and the careless discarding of agents we disqualify as things unworthy of either care or respect. In that sense the novel is a new type of mirror, using the figure of the robot to tell us things about our selves we may prefer to ignore. My problem is that in projecting our own agency on humanoid robots the author may contribute to fatal misunderstandings about the nature of artificial intelligence and thus lead us astray, for instance by providing support for the attribution of legal personhood on grounds that cannot be substantiated. I believe that Richard Powers’ Galatea 2.2 (1995) provided a much more salient narrative on the potential of an emergent computational agency based on artificial neural networks, less easy to consume, but both more imaginative and more precise in its portrayal of what these ‘systems’ may be capable of and what not. I made an in-depth study of Powers’ work, as part of the edited volume on Human Law and Computer Law, celebrating Powers’ ability to suggest the sweet pain of a disembodied agent as well as a sober accounting of what machine agency actually does. Whereas Powers deploys irony while introducing the paradoxes of ‘believing’ in machine agency, Ishiguro’s work leaves the reader with a weighty kind of sadness, precisely because there is no way to doubt the existence of an inner self in Klara, no attempt to call out the unsubstantiated claims of those who avow their contraptions are indeed like us.

So, I have my qualms, but there are many reasons to admire and appreciate the narrative as it stands. Luckily, it is not the task of an author to educate people on what AI means, what it can do for us and whether it can actually think or feel in ways we could even perceive as such. It is via the figure of the robot that Ishiguro raises myriad salient questions without resorting to the more cerebral inquiry that is Powers’ signature genre. Ishiguro knows he must ‘show not tell’ to persuade his audience. And I must admit I used a similar figure in my 2015 Christmas Essay for the Belgium newspaper De Standaard, building on the narrative that opens Smart Technologies and the End(s) of Law.

Thomas More - Utopia (Penguin Classics 1516) [I]

Can our writings favor coexistence and meet demands of our time? Can they contribute to composition of a common world? and how? This question truly captured me this year (as you may notice from my reviews that are all linked to each other).

It seems that Aristotle said that when we remain vigilant we have a common world, but when we dream each one has his own world (practitioners of meditation and some psychanalysts may have a similar view). At the same time, political thought has often turned to imaginary lands to propose ideal versions of the common living.

Everyone knows Utopia (1516) written by Thomas More, the English humanist, philosopher, jurist, and politician. The book is an important political and literary contribution. It draws from previous theorizations of ideal cities (Plato, Augustine) and paves the way to a genre that became much cultivated in modern times: the fantastic description of a non-existent world and political organization; a practice later inherited by Science Fiction.

Utopia is an imaginary and good island (u-eu). But More did not intend it as an escape from reality. On the contrary, as he wrote at times of religious violence and social division, he saw his description of alternative political and legal set-ups as serious commitment to trigger reform in England. Utopia is thus proposed as the model of “the best state of a Republic”: a serene and wise civilization, respectful of humans, aware of their inner complexity, grounded on diversity of beliefs, reason and tolerance.

Voltaire - Candide (Edition by Sylviane Leoni, Le Livre de Poche 1995) [II]

In 1759, during the Enlightenment, the topic of the best of the possible worlds is famously picked up again by Voltaire in Candide. Here, however, it is proposed in caricatural key through a mix of imaginary and realistic elements. The naïve protagonists always end-up leaving serene or ideal places (the Castle, Eldorado) out of force or wishful thinking. By travelling the real world, they acquire some knowledge and even (limited) wisdom. Voltaire turns to experience to reconcile them with reality. He offers a disillusioned picture of human reason and the world. In the end, there is no best possible world, despite initial presumptions and optimist speech on its actual existence.

‘Penser avec Donna Haraway’ – under direction of Elsa Dorlin and Éva Rodriguez (PUF 2012) [III]

Today, ecofeminist authors invite those concerned with co-existence in our time to engage with many versions of SF. They encourage the construction of possible, material-semiotic worlds that have disappeared, or exist, or that have yet to come. Affects (that have kept political theorists busy since the Greeks) re-enter the picture in new manners, reminding us that beyond reason is body, and body is nature and culture, and hybridity, relations, life, and partial connections. We are far here from an imagined and redeemed world, as well as from sceptical versions of it. We are done with concepts such as tolerance and innocence as we need other ways to think to avoid prejudice and shortcuts.

We are asked to situate ourselves concretely and somewhere in the existing world, where a role for imagination remains “for earthly survival”. In this attitude demanding commitment lay important alternatives to violence, repression, and extinction. I remember another contemporary thinker saying: just describe. Describe a concrete state of affairs, but do it through a peculiar movement of re-association, as the common world has still to be collected and composed. Here is where I find an alternative to critique, guilt, and scepticism: in an attitude freed from presumption, demanding attentiveness, openness, and genuine curiosity.

Privacy at the Margins - Scott Skinner-Thompson (Cambridge University Press 2020)

This is such a great book. It is one of those books which are full of fascinating ideas and extremely rich in interesting references, so whenever you read it you might find yourself mentally jumping from one thought to another, and then suddenly into another book, another day. I actually started jumping around with joy when I saw the title: ‘Privacy at the Margins’. Yes, we need more privacy at the margins. We know it: society likes to keep at its margins whoever does not fit. The poor. The foreign. People with disabilities. Queer folk, including trans and gender nonconforming individuals. Whoever looks different, or thinks or feels differently, or has different beliefs, faith, or sexual preferences, and/or less money. The other, whatever that might mean: we will label them as such, treat them as such, and, for sure, keep an (extra) eye on them. Often, society will argue it must place them under greater scrutiny to protect them from themselves – explaining, for instance, that the state needs to double check the intimate parts or hormone levels of people wishing to rectify a gender that was once assigned to them, just in case they might be temporally confused, and hurt themselves forever. We know marginalised communities are systematically placed under greater surveillance. Nevertheless, many appear to have given up on their right to privacy, as if privacy was passé, or not a key right for them. ‘Privacy at the Margins’ explains why we cannot afford to do that. And it does so brilliantly. It might demand some extra effort from the European reader (as Julien Rossi noted in his review for European Data Protection Law (EDPL), the book is deeply entrenched in American doctrine), but it is absolutely worthwhile.

Helen Joyce - TRANS: When Ideology Meets Reality (London: Oneworld Publications 2021)

In her best-selling, thoroughly researched and controversial book, The Economist journalist Helen Joyce deals with one of the hottest topics currently debated in the "Anglo-sphere", i.e., gender identity, and, to be more precise, whether or not male-bodied persons can legitimately expect to be treated as women in all aspects of life solely based on self-identification. Should a male-bodied person, i.e., with male genitalia, have the right to enter women-only spaces, such as changing rooms, public toilets, refuges for women victims of violence or female prisons? Should a person who went through puberty as a male be allowed to compete in sports under the “women” category? Perhaps most importantly: should children of one sex who exhibit behaviours of the opposite sex be encouraged in thinking that they "really" belong to the opposite sex and be administered puberty blockers and cross-hormones and undergo surgery?

Helen Joyce’s answer to all those questions is a resounding “no”, which puts her, in the eyes of those who think that the answer is “yes”, firmly in the camp of the "TERFs" (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists) or, more politely, "gender critical feminists". Joyce proceeds by drawing the history of the trans issue since the first person to undergo surgery to change sex, i.e., Danish artist Lili Elbe (born Einar Wegener), whose story was depicted in the movie "The Danish Girl" a few years ago, to the current stand-off between Trans Rights Activists (TRAs) and gender critical feminists. The author also identifies some of the main players in the promotion of the agenda of TRAs and analyses stories collected from the news and other sources that illustrate the problems the presence of male-bodied persons in women-only spaces give rise to. Though she could have spent perhaps more time in showing the connections to identity politics or to the wider “social justice” movement, I think Joyce’s is a very important book and I would definitely recommend reading it.

Radu Jude - Tipografic majuscule (Uppercase Print 2020) (film)

During the whole month of August 2021, I recommended every day on Twitter a film about surveillance and/or privacy (an expanded list of recommendations can be found here). To choose them, I watched and re-watched many films. I repeatedly visited the local multimedia library to rent DVDs. I opened all the boxes where I keep my own. I ordered new ones from obscure online stores, and from Amazon. I went to the cinema. I watched documentaries on my favourite documentary online platform and registered to unknown online streaming services. I used the Netflix subscription of a distant relative. I borrowed a videocassette recorder. I watched TV. I did lengthy searches on the Internet Archive, and on all online public repositories and websites of relevant institutions I could think of, from the National Film Board of Canada to La Cinémathèque française, as well as on P2P networks. I watched YouTube. A lot. In short, I watched many films, and it is very hard for me to pick up now one from that period, as I enjoyed the whole experience as a process, and I am convinced that, by watching many diverse films about the same subject in a relatively short lapse of time, my brain managed to see connections it would have never seen otherwise – coinciding messages about how surveillance operates, and what it does to people. As I cannot mention them all, I will single out ‘Tipografic majuscul’ (Uppercase Print), an excellent 2020 Romanian film by Radu Jude. Combining theatrical reconstructions and excerpts of vintage TV, it tells the story of Mugur Călinescu, a teenager who wrote chalk graffiti calling for freedom in 1981, and how the ensuing investigation destroyed his life, and his family. But, really, I recommend them all.

Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar - The Time Regulation Institute (Penguin Modern Classics 2014)

I read this classic of Turkish literature in my Summer vacation (in Turkey) and enjoyed it immensely. Set in Istanbul of the early 20th century, Tanpinar brings to life the clash between old and new ways of being and living together in a compelling and humorous story about modernization. The book is centered around our experience and handling of time and infrastructures for the management of time.

Standardized time regulation remains an interesting phenomenon today. It’s an area in which quantum (sensing) technologies, one of my research interests, play a significant role. Tanpinar’s classic helped me to understand the extent to which our current experience of time relies on a complex set of socio-technical and socio-legal practices which continue to evolve.

Shani Orgad - Heading Home: Motherhood, Work, and the Failed Promise of Equality (Columbia University Press 2019)

The book explores and illuminates the failure of western societies to live up to the promise of equal treatment of working mothers. Through a series of interviews and media and policy analysis, the author shows how the narratives of self-empowerment and work-life balance place the burden on the individual, distracting and disorientating policy makers from addressing the deeply rooted systemic and structural problems that foster gender injustice. A fascinating study discussing reasons of the growing phenomenon of educated women in western privileged societies leaving paid employment out of what is erroneously thought to be a personal choice.

A nice book review can be found here.

Pauline Moulin - BierWandelboek België: een verfrissende manier om België te ontdekken (Uitgeverij Luster 2019)

A considerable part of living in another country is to experience the local culture. In my opinion, food and drink are perhaps one of the most relevant aspects where one is actually immersed, willingly or not, into that different culture; after all, any human still has to eat and/or drink something, at least, every now and then. In that respect, it is impossible to deny that beer has a central role in Belgian culture.

The book focuses on certain Belgian cities and towns associated to a distinct and iconic beer. It provides a detailed walking tour, either rural or city-focused, with the highlights, such as museums, landmarks, etc. of that place, as well as information of the beer in question. The routes begin or end, depending on the case, in the relevant brewery. As such, it provides a twist on the traditional (and honestly, boring) travel guide. During a year where international travel was (and will still be) complicated, exploring local places was a much-welcomed activity to leave the house and experience a country that 2020 put on hold.

Samantha Schweblin -Little Eyes (Oneworld 2018)

Samantha Schweblin is one of my new favourite authors that I discovered this year thanks to the various book clubs I like to attend (I can also wholly recommend her ‘Fever Dreams’). I was therefore beyond enthused when I discovered that she wrote a novel relevant to privacy and surveillance. ‘Little eyes’ explores the effects of a camera equipped pet-toy that is being introduced all around the globe. The toy serves as a human pet for the person buying it but also enables the person controlling the pet and its camera remotely to participate in the life of another human being. The novel beautifully illustrates the effects and potential unwanted consequences of surveillance in the private home for both the person under surveillance and the person in charge of it. Better than any report or court case it made me realise the importance of all the boundaries the right to privacy should afford us in light of modern technologies.

Muriel Spark - Memento Mori (Polygon Books 2017)

‘Memento Mori’ by Muriel Spark is a very funny book (if you like dark humour like I do) but it is also a thoughtful exploration of life and death and the interrelation between the two. The premise of the book is simple: a collection of different elderly Britons start receiving phone calls that convey the message ‘Remember you must die’. This triggers different reactions among the protagonists, from fear and police investigations to life-altering decisions. In the end, the book leaves the reader with an appreciation of the preciousness of life and all its ups and downs, but also of death and its meaning for life.

Douglas Stuart - Shuggie Bain (Picador 2020)

Shuggie Bain won the 2020 Booker Prize, and as an authorial debut it’s a fantastic achievement that deserves much of the praise it has received. The story is a moving semi-auto-biographical tale of Shuggie (Hugh), a misfit boy navigating the pains of growth and self-understanding in the harsh world of 1980s post-industrial Glasgow. The story is not light: Stuart’s themes include desperate urban poverty (the precarious search for coins to top up the electricity meter is a daily concern), navigating the norms of integration in wary working-class communities scarred by neglect, and the confusions and yearnings of finding out who we are and what we want – especially so for Shuggie, who knows he’s different from other boys but can’t quite make sense of how, or why. Simultaneously, the sweetness of childhood innocence and Shuggie’s bottomless love for his mother are made all the more poignant in the face of his powerlessness to do anything about her advancing alcoholism. All this takes place under the claustrophobic fog of a Glaswegian culture that hasn’t yet come to terms with emerging ideas of malehood that don’t fit the stoic template associated with Clydeside.

This is a beautiful, raw book that highlights the challenges of working-class lives, at a place where and at a time when the combined effects of Thatcherite de-industrialisation and a culture of repression (of many forms) were especially harmful. But it’s also a statement of the power of love to endure and to deepen, whatever – and perhaps sometimes because of – the material and social circumstances we find ourselves in.

Lana Swartz - New money: how payment became social media (Yale University Press 2020)

I believe that I finished this book in a single weekend (although I’m coming and going to it often). Swartz’s book provided me with so many ideas and paths to explore as a researcher looking at this weird intersection between money and technology. She argues that money and, more in particularly, payments allow for communication rather than simply being a way to transfer value. As such, how monetary and payment infrastructures are configured determines how and what, among many other issues, can be said, but also who can speak to whom.

Her work comes timely as most jurisdictions, including the EU, are debating about the very core of the financial services system as they are engaging with issues such as central bank digital currencies, API-based and data-driven open finance initiatives, cryptocurrencies, the use of digital identity wallets to facilitate Know Your Customer policies, etc. All of these innovations have a different take on how ‘transactional communities’ should be built and how ‘transactional communication’ should be done: anonymous vs. known identities; backed by governments vs. supported only by private sector; mass vs niche platforms, among many other possible discussions.

I wouldn’t do justice to the book by trying to summarise it in fewer than 300 words, but I do believe that this is a must-read for anybody researching about finance and technology, regardless of the discipline.

Bryant Terry (curator and editor) - Black Food. Stories, Art & Recipes from Across the African Diaspora, 4 color books (imprint of Ten Speed Press, California, New York 2021)

This work is an ode to real life, to the materiality of human agency and to the diversity of black food in the African diaspora. As Feuerbach noted in full and serious irony, ‘Der Mensch ist was er ißt’, integrating materialism and scientific acuity with a political consciousness that nourished the young Karl Marx and many others. This is not a collection of trendy African recipes updated for the hipster book market, but a Gesamtkunstwerk giving voice to writers, artists, scholars, chefs, great-grandmothers, chiefs and many others, celebrating and cultivating a long-standing heritage of migration within and without Africa, bound by the roots, seeds, grains and leaves that ground the culinary traditions and revolutions of those descending from the African continent, their myriad cultures (= practices) and communal identifications (imposed as well as chosen). As Freda Moyambo writes ‘I am because we are’, recognising the relational nature of embodied human cognition in the pleasures and constraints of both preparing and sharing the food of the motherland, to which she returned from Australia. Sensuous, activist, political, tasty and colourful, Bryant Terry’s Black Food honours, explains, tells and shows what Amartya Sen might call the ‘doings and beings’ of a diverse people that find themselves in a diaspora – tracing themselves to slavery, injustice and humiliation but also to a deliciously adaptive culinary tradition that informed so many other culinary traditions, even if credit has not been given. This is not an attempt to endorse what some call ‘learned helplessness’, and neither a glorification of black suffering nor a call for retribution, but a dedicated revelling in the generous legacy of African food styles and all they give. And yes, there is violence in the call for resilience, for making one’s voice heard, for taking food seriously.

This book was a gift from one of my two much loved and ingenious daughters, an unexpected trove of narratives, a palimpsest of overlapping perspectives. Read, enjoy, learn and try them out, because this work also includes the most practical knowledge we have: algorithms to prepare food with (more often called recipes). Just saying, the tacit knowledge that is presented in this volume also reminds us of the limitations of algorithms that must comply with the constraints of Boolean algebra.

Florian Zeller’s 2021 movie The Father, after the namesake play (also by Florian Zeller), starring Anthony Arthur Hopkins, Olivia Colman and Imogen Poots

Old age and its discomforts. When my ex-husband was dying, I was on the verge of teaching a class in the European Academy of Legal Theory – I had to tell my students the class was cancelled, but I could not find my voice when they entered the classroom. They were shocked to see my pain and found their professor crying instead of speaking. Two African students walked me to the bus, on my way to the final encounter with the father of my daughters. They comforted me and said that in their homeland people would say I was in another time zone. And so I was. The confrontation with death takes us out of ordinary time, it removes anything and everything that is normal and expected and foreseeable, even though death is – as the cliché goes – the only certainty in life.

In The Father, Zeller plays tricks on the viewer’s sense of time, forcing upon them the disruptive un-timing of those suffering from Alzheimer’s or other root causes of dementia. Magnificent acting by Anthony Hopkins, who presents us with a grumpy, intimidating and seemingly misogynist father, who can nevertheless also be charming and has arrived at a point of painful vulnerability. The father inhabits his monumental London apartment, where he mourns the receding power and control he must have once held over other people. By now, he is navigating an increasingly unfamiliar space that apparently takes him – and us, the viewers - for a ride by rearranging objects, persons and events. The movie is brilliant in destabilising the viewers’ own sense of time and space, eliciting both irritation and a sense of loss. The father’s caretaking daughter is played in a supercalifragilisticexpialidocious way by Olivia Colman, who recently starred in the film adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter (2021). In The Father, the caretaker daughter will be moving to Paris to start a new life. She is hiring a carer, but her father intimidates, violates and humiliates the carer such that she leaves in tears. The next carer is played fabulously - sorry for the superlatives – by Imogen Poots, who recently starred in David Lynch’s horrific Vivarium (2020). This carer takes a fancy to the old man and they hit it off well. The situation becomes, however, untenable, and the movie shows where this ends – perhaps conciliating estrangement with comfort, if that were possible.

Since Michael Haneke’s Amour (2012) I have not seen such an incisive portrayal of human fragility and love in the face of the abyss of dementia, where death becomes a gift to be embraced or a plan that must be secured. Perhaps the difference between AI systems, however sophisticated, and human agents is our ability to suffer, to become aware of our own mortality and to witness the decline of our own agency. This is precisely why I am worried about Kazuo Ishiguro’s most recent novel, one of the other books I discuss here.

Yoko Ogawa - The Memory Police (Penguin Random House 1994, English translation by Stephen Snyder 2019)

“And what will happen if words disappear?” I whispered to myself, afraid that if I said it too loudly, it might come true.

This is a book that kept me thinking long after I read it. Yoko Ogawa wrote this novel as a response to her reading of Anne Frank’s diary. The book was first published in Japan in the early 1990s during a time where Japanese society had just started cracking open the discussion around the role of the country in past atrocities. The author confronts the reader with the possibility that everything can disappear from one day to another: from birds to boats, from books to photographs, from maps to musical instruments, from smells to foods, from calendars to statues, from persons to one’s own voice, to one’s own memory. There are two overarching questions: when does something indeed disappear -- when the thing itself is gone, or when its memory is gone? And what are the consequences of those disappearances to the society (present and future) and to the people who experience them? The book explores the invisible processes of memory, forgetting, loss and narrative from many different aspects - political, historical, societal and individual - through a dystopian tale of an unnamed island, its deprived population and the Memory Police, entrusted with the task of enforcing the disappearances.

Editors

LSTS books (and more) of the year 2021 was edited by Laura Drechsler, Laurence Diver and Olga Gkotsopoulou.

Accompanying pictures are included for illustration and may or may not correspond to the cover of the edition the reviewer actually read, watched or listened too.